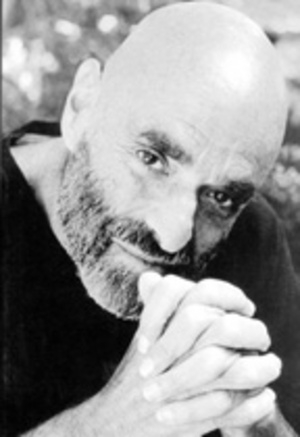

Shel Silverstein opens his first book of poetry, Where the Sidewalk Ends, with a poem stating “If you are a dreamer. . . come in,” inviting readers into his crazy and creative world of poetry. As a young child I was always entertained by Shel Silverstein’s humor and fun with language, and even as a young adult his writing never ceases to make me laugh. Silverstein incorporated specific techniques into his writing to make his style so humorous.

Exaggeration, irony, and the reversal of letters in words all add to Silverstein’s humorous writing style. Expanding the magnitude of something that is usually quite trivial can be a fun way to create humor, and this style of writing is frequently found throughout Silverstein’s literary works. In the poem “Sarah Cynthia Sylvia Stout Would Not Take the Garbage Out” from Where the Sidewalk Ends, Sarah refuses to take the garbage out until so much garbage accumulates that it “rolled on down the hall,/ it raised the roof, it broke the wall” (lines 21-22). When she finally gives in and says that she will take it out it is too late-“The garbage reached across the state, / from New York to the Golden Gate” (40-41). Silverstein even adds a warning to all children to “always take the garbage out” (47) which is humorous to both children and parents alike because parents are always nagging their kids to do their chores.

The poem “The Dirtiest Man in the World” also contains many examples of exaggeration. In this poem Dirty Dan explains rather nonchalantly “I can’t see my shirt – it’s so covered with dirt, / And my ears have enough to grow flowers (lines 3-4). Shel Silverstein took the very obvious characteristic of Dirty Dan to the extreme. He even goes on further to explain:

If you looked down my throat with a flashlight, you’d note

That my insides are coated with rust.

I creak when I walk and squeak when I talk,

And each time I sneeze I blow dust (15-18).

These “symptoms” of being dirty are probably impossible to get, but the use of such ridiculous exaggeration makes the poem as hilarious as it is. It would not be the same if Silverstein simply said, “he smelled.” Rather he says, “when people have something to tell me / They don’t come and tell it – They stand back and yell it” (20-21) adding to the humorous nature of the story.

In “It’s Hot” from A Light in the Attic the temperature is so hot that the narrator has tried everything to stay cool including taking all of his clothes off, but he continues to be hot. He decides to take his skin off and sit around in his bones (84). Silverstein once again goes to the extreme with this poem, having a situation that is usually quite trivial and taking it as far as he possibly can.

Shel Silverstein’s use of exaggeration is also present in the lighthearted poem “Sick,” which is also found in Where the Sidewalk Ends. Peggy Ann McKay explains that she cannot go to school because she is just too sick. She describes her ailments, both common and bizarre, in the following exaggerated way:

I have the measles and the mumps,

A gash, a rash and purple bumps,

My mouth is wet, my throat is dry,

I’m going blind in my right eye.

My Tonsils are as big as rocks,

I’ve counted sixteen chicken pox... (3-8).

Peggy Ann McKay continues to describe her phony ailments that prevent her from going to school, but the funniest part is the dramatic turn at the end when she says, “What’s that? What’s that you say? / You say today is…Saturday? / G’bye, I’m going out to play!” (lines 30-32) She is miraculously freed of all symptoms. This brings into effect another technique Shel Silverstein used to produce humor in his writing – irony.

Shel Silverstein attempts to quickly destroy any assumptions that the reader makes during the poem with an ironic twist that will have the reader laughing. For example, in the poem “Fancy Dive” from A Light in the Attic, Melissa dives the best dive ever dove, but it is not until the very last line that the reader discovers there is no water in the pool. “Messy Room” is similar in that the narrator is appalled by how messy a certain room is, but it is not until the end of the poem that he realizes that it was his room that was so messy all along. He simply states, “I knew it looked familiar!” (line 16). In “Invention,” from Where the Sidewalk Ends, the narrator has invented the most phenomenal device-“a light that plugs into the sun” (line 3). Everything is perfect except for one thing… “The cord ain’t long enough” (7). In “Smart” a father gives a dollar bill to his “smartest” son, but the boy trades it for two quarters “Cause two is more than one!” (line 4). He continues to trade the two quarters for three dimes, and so on until he is only left with five pennies. He proudly goes to show his dad and explains that he “closed his eyes and shook his head- / too proud of me to speak” (19-20). The young boy in this poem obviously has no concept of the value of money, but he is thrilled with the exchanges he made. Little does he know that although he brought back more coins than he started with, the value is much less.

One final example of irony is included in Shel Silverstein’s most popular book, The Giving Tree. In The Giving Tree, the tree gives the boy anything he needs out of love. She willingly meets his most important needs: food to satisfy his hunger, shelter under which to rest his tired body, and companionship. She even offers her branches for him to build a house and her trunk to build a boat. Even when she is nothing but a stump, she offers him a place to sit and rest… “And the tree was happy.” This is ironic because not once did the tree get angry or sad, but rather happy-giving herself to him was in fact, her deepest fulfillment (Werpehowski).

In his most recent book, Runny Babbit: A Billy Sook, Silverstein inverts the first letter of each of a two-word string so that “bunny rabbit” becomes “runny babbit” and so on. The opening poem in this book explains this crazy way of talking very clearly:

Instead of sayin’ “purple hat,”

They all say “hurple pat.”

Instead of sayin’ ‘feed the cat,”

They just say ‘ceed the fat.”

So if you say, “Let’s bead a rook

That’s as billy as can see,”

You’re talkin’ Runny Babbit talk,

Just like mim and he.”

It’s difficult not to laugh at reversals like “sea poup” or “ficken charmer” even as an adult. Just think of how these would sound to a child on the verge of helpless laughter. Silverstein’s more interested in creating novel sounds and finding new ways to add humor into his poetry (Weinman). In reading through each poem, the mind automatically puts the letters back in their proper place, so that the poems read perfectly well on their own, “showcasing Silverstein’s trademark playfulness, humor, and his innate ability to capture the thought patterns and rhythms inherent to young children” (Weinman).

Silverstein’s illustrations also add another dimension of humor to his literary works. Some of his writing would not be as humorous without an accompanying black and white line drawing. Many times these illustrations depict the meaning of the writing while adding an extra punch line. For instance, “Pancake?” is a poem that is simply asking who would like a pancake. Good little Grace says that she will take one from the top, but Terrible Theresa smiles and says “I’ll take the one in the middle” (Where the Sidewalk Ends, 34). If the illustration of pancakes stacked to the ceiling was not accompanying this poem it would not be funny and it would not make sense to the reader. The same is true for “Something Missing” in which a man has a feeling that he forgot to put something on, but he cannot figure out what it is. He goes through a list of things he is sure he put on and explains, “I feel there is something I may have forgot-What is it? What is it?…” (A Light in the Attic, 26). The accompanying illustration shows him wearing everything… except his pants, which is difficult for the reader not to laugh at.

During a career that spanned much of the last century, Shel Silverstein sold over 20 million books, which address the deep feelings, joys, and fears of everyday life in a humorous way (Livingston). He has also received numerous awards for his humorous style including the New York Times Outstanding Book Award for Where The Sidewalk Ends, Michigan Young Readers’ Award for Where The Sidewalk Ends, School Library Journal Best Books Award for A Light In The Attic, the Quill Award for Children’s Illustrated Book for Runny Babbit: A Billy Sook, and many others (“Biography”).

No poet has touched children’s lives more than Shel Silverstein through his fun with language (Livingston). After exploring Silverstein’s literary works, one can better appreciate the humorous style in which Silverstein writes. Exaggeration, irony, and the reversal of letters make Silverstein’s writing easy and fun to read. It is no wonder why he is such a successful writer.

“Biography.” Shel Silverstein. 13 Sept. 1997. 20 Apr. 2006 .

Livingston, Myra C. Shel Silverstein. 9 Mar. 1986. 9 Apr. 2006 .

Silverstein, Shel. A Light in the Attic. New York: HarperCollins, 1981. 7-169.

Silverstein, Shel. Runny Babbit: a Billy Sook. New York: HarperCollins, 2005. 7-96.

Silverstein, Shel. The Giving Tree. Harper & Row, 1964.

Silverstein, Shel. Where the Sidewalk Ends. New York: HarperCollins, 1974. 9-166.

Weinman, Sarah. ” The New Switcheroo.” PopMatters. 19 Apr. 2005. 9 Apr. 2006 .

Werpehowski, William. “The Giving Tree: a Symposium.” First Things. Jan. 1995. 20 Apr. 2006 .