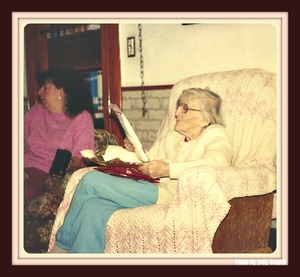

It was the winter of 1991. We were watching television, Alpha Mae and I, a western movie about a time from the annals of American history. She sat in the recliner across the living-room, her white head glued to the television set, her small bent frame at ease in the over-sized chair, her aged face, a parchment of wrinkled leather, but her eyes, those bright, perceptive eyes turned on me and she boldly stated, “I walked from Kansas to Colorado beside one of those when I was ten years old.”

I glanced back at the TV, which I’d only been paying attention to with half of my mind while I crocheted an afghan I intended for a Christmas gift. ‘Beside what’ was my first thought, and there on the screen was a row of dusty wagons pulled by teams of horses or oxen, filing through some rough, dry looking terrain.

“A conestoga wagon?” I asked her.

“Those things there,” she pointed towards the television.

“You’re kidding, right?” I chuckled, but even as I said it, I knew she wasn’t. I was doing my mental math. Alpha Mae was 88 years old. This wizened little woman would have been ten years old in 1917.

“Wow, Alphie Mae, what was it like?” I wanted to know, curious to hear her story. Alpha Mae came to be an extended member of my family when she was already quite elderly. She was fostered by my sister and her husband when DHS (the Department of Human Services) found out Alphie Mae was living alone. At the time DHS didn’t believe she was capapble of taking care of herself any longer. Their solution was going to be to put her in a nursing home. My mom, when she discovered what they were up to, convinced DHS Alphie Mae didn’t belong in a nursing home, and persuaded them to make arrangements for her to live with Marion and Monroe instead. Truthfully, I knew very little about the woman even though she’d lived with Marion and Monroe for several years now.

While Alphie was usually a very laid-back, quiet individual, suddenly, she was quite animated and fervidly ready to share her story. “We thought we’d die of thirst,” she baldly stated.

“You ran out of water?” I asked.

Alphie nodded her head, “Yep, the water was stored in a barrel on the back side of the wagon. I don’t know how many days it was but several, maybe a couple of weeks, and there was no rain. The water holes were dry. At first my dad let me ride in the wagon. Then he made me get off and walk to make it easier on the horses.”

“Where was your mother?” I inquired.

She died in childbirth that winter before we left Kansas City. We were stayin’ in a sleepin’-room in a boardin’ house alongside the Kansas River when Mama went into labor. She was so happy to be havin’ a baby again after all those years. After I was born she thought maybe she’d never have another. But something went wrong. When Daddy couldn’t deliver the baby, he looked up a midwife. At first the midwife thought she could save Mama and the baby both. But by the end of the second day, when Mama was too worn out to keep pushin’, we all knew we were just waitin’ for Mama to die, and she was takin’ the baby with her.”

“That was in February.” Alpha Mae delivered this matter-of-factly, but I offered condolences just the same. Alphie shrugged her shoulders, and it occurred to me this was ancient history for her.

“Daddy was workin’ on the Kansas River, loadin’ barges to pay for our room and board at the boardin’ house. I could walk down to the docks and watch him work on days when the weather was decent. The Kansas River was one beautiful body of water. It was always a busy place with large boats dockin’ or pullin’ out. I saw fishermen pull some of the biggest fish out of there I ever saw in my life, some as long as a man is tall.”

“One day my daddy came back to the boardin’ house, all excited. Alpha Mae, I’ve found a wagon master who’s puttin’ together a wagon train headin’ west. He says they’ll be movin’ out in March as soon as spring thaw. That gives me time to locate a wagon, a team of horses, and lay in supplies for the trip.”

I thought of my mama and my baby brother or sister laying in the frozen ground at the Union Cemetery, already grieving for what we’d be leaving behind.

“Now don’t be lookin’ at me like that, girl! There’s nothing keepin’ us here and this is our chance to have somethin’ of our own! We gotta grab it and go!” my daddy said. “This could be the last wagon train headin’ west in our lifetime, Alphie Mae.”

“I knew come March we’d be leavin’ on that wagon train headin’ west, and we were.”

I wanted to encourage her to keep talking. “How many wagons were in the wagon train, Alphie Mae?” To think, this little lady sitting in my mom’s living-room was a genuine pioneer, with a life-time of stories to share and I’d never asked her anything about any of them.

“Can’t rightly recollect now, but I’m guessing maybe 18. Enough we felt safe in a crowd, but it turned out, we weren’t all that well off after all.”

“Why? What happened, Alphie?” She had me spell-bound by now. “Don’t go gettin’ the horse ahead of the cart, Missy,” she teased. “Now where was I?”

“Oh, yeh! It took every dime my daddy had to get us a rig and supplies. I seem to recollect he paid $400.00 for the wagon, and that was a small fortune at the time. The canvas wagon top had to be treated with linseed oil to make it waterproof as possible. We packed the wagon with flour, lard, bacon, beans, fruit, coffee and salt. We took as much as we could afford when we left Kansas City, and sometimes Daddy would do ‘handy man’ work for a farmer or a merchant along the way, and trade labor for food goods. Daddy was never afraid of a hard day’s work.”

The wagon also had to carry cookin’ utentsils, tools like a shovel, an ax, a saw, things we’d need to build a cabin when we got to Colorado and to plant a garden.”

“When we left Kansas City, it was early spring. I’ll never forget that first mornin’ at the edge of the woods along the Kansas River. As far as the eye could see, the white canvas covers stretched on either side of us. The wagons were in scattered groups around several campfires. Most everybody was cookin’ their breakfasts so wood smoke was drifitin’ over the camp ground and womenfolk were tryin’ to keep an eye on their children runnin’ around like wild Indians. Some of the menfolk were ridin’ herd on cattle grazin’ along side of the river. You could feel the excitement buzzin’ through the camp. Everybody knew we’d be headin’ out shortly.”

As soon as dishes was washed and loaded in the wagons the wagon master shouted, ‘Head ’em up, move ’em out!’ and I was seated proudly on the wagon seat next to Daddy, tryin’ not to cry about leavin’ Mama all by her lonesome in Kansas City. I guess it maybe gave me a little comfort to think the baby was stayin’ with her. I never figured I’d ever be seein’ that lonely grave again in my lifetime.”

“It was excitin’ too though. You had the feelin’ something important was happenin’.”

“At first the grass was lush and green on the rollin’ hills around Kansas City. We could travel maybe 15 to 20 miles a day. Spring bird song woke us up every mornin’, and coyote’s sung us to sleep every night. But then the landscape started changin’.”

“It was turnin’ hot, hot and dusty, and and I started to notice we hadn’t come across anybody, no farms, no towns, for days!” Alphie recalled. “Occasionally, we saw a band of Indians along side of the trail. We were scared of them because we’d all heard some wild stories, but it turned out it wasn’t the Indians we should have been scared of. When it happened, we never even got to circle the wagons and defend ourselves.”

I stared at her transfixed.

“A gang of bandits, maybe 5 or 6 of them, came out of nowhere. At first we couldn’t see what was goin’ on, nothin’ except the dust from a band of horses and riders movin’ towards us. We didn’t know it was an attack until we heard a little child scream as if the hounds of hell were after it. Then a woman was shriekin’. Maybe it was the mother. My Daddy leaped from the wagon, and called to me to get down and under the wagon while he pulled his rifle from it’s scabbard alongside the wagon seat. My Daddy produced a knife in his free hand from somewhere and headed in the direction of the fightin’.”

“He was still close enough I could see when he was tackled by one of the hooligans and fell to the ground. Using his rifle for a club, he brought it around and hammered the burly desperado alongside of the skull with it. Daddy jumped to his feet, still holding the rifle like a club, but the gangster was down for the count. We could hear yellin’ and screamin’ in the distance, and I saw my daddy take off at a dead run to where it was comin’ from.”

“After that I couldn’t see anything, just hear the yellin’ and screamin’. I decided I was not in a safe place and creeped from the trail and into the shelter of some juttin’ rocks and a few scraggly bushes a few feet from where our wagon was still parked. I could now see my daddy wrestlin’ with a ganster up ahead, but it was a short fight. There were some bodies layin’ on the ground, and shortly, my daddy was sittin’ on the ground, tied to a wagon wheel, and the bandits were lootin’ everything in sight.”

“I don’t know how long it was but it seemed like hours I hid there waitin’ for the remainin’ thieves to be done with their lootin’ and head out. At one point one of them was standin’ so close I could’ve spit on him if I’d had the courage, but I was so scared I was shakin’ where I sat. He found a locket that belonged to my mama, but besides that, we didn’t have any valuables to speak of. The things in the wagon were to set up house-keepin’ and he kicked the wagon wheel in disgust and moved on.”

“It was dark by the time they climbed into their saddles and headed east in a cloud of dust, pullin’ a couple of horses they’d stolen from one of the families in the wagon train behind them.”

“Finally, when they were only little specks in the dark, I crept out and started lookin’ for survivors. Daddy was slumped over, still tied to the wagon wheel, but he started moanin’ and groanin’ when I loosened the ropes holdin’ him up. Together, we found the wagon master, shot through the gut and in the shoulder. He was already gone. Two other men had been wounded, but Daddy was able to patch them up.

“The hooligans, they’d hit us hard. They took our money and all the supplies they could carry and they’d left us to die out there.”

“What did you do then, Alphie?”

“Dad dumped everything he could from our wagon, not just Dad, everybody did, the heavy furniture, anything that would weigh a team down. Just left it sitting along side the trail, and we started walkin’ again.”

“Those that could keep goin’, they joined us.”

“Did you ever think about turning around and going back?” I asked.

“No. By then we’d come too far to go back. Eventually we found water, rested the team, and we kept walkin’. By then I’d worn out the shoes I had when we left Kansas. I went barefoot until my Dad was able to scrounge up some rawhide and then I made myself some makeshift moccasins. Sometimes my dad was able to shoot some wild game for a meal. Sometimes he wasn’t. We’d share what we got with those left because they shared with us.”

“How long did it take to get to Colorado, Alphie Mae?” I was shaking my head in amazement.

“Months, I reckon. It was March when we left Kansas. There was snow on the ground in Colorado when we got there. One of the men stayed long enough to help my dad drop enough trees to build a small cabin, and in turn my dad helped him build one. That first winter was rough though.”

“How did you survive it?” I shook my head in amazement.

Dad built a fireplace out of river rocks. The cabin was only one small room. We packed clay and mud between the logs to keep the weather out. Once the first freeze came, the mud chinking got hard as a rock. We didn’t have much food though except for what Daddy could hunt or trap, but it was enough. By spring we could forage for food the way the wild animals did. We could fish, and Daddy knew a little bit about wild roots the Indians ate. We gathered acorns and nuts, and picked wild blackberries when they set on.”

“Did you ever make it back to see your mama’s grave, Alphie Mae,” I asked, my admiration for this tiny little lady having just taken on new proportions.

“Once, after I was married, my husband took me back to check up on it,” Alphie Mae nodded. “The cemetery had grown so large by then, we had a heck of a time finding it. It was only marked by a good-sized stone, and a wrought-iron cross my daddy had welded at the local blacksmith’s shop that spring before we left. But that was enough. I knew it when I saw it. It was a one-of-a-kind marker, turned and twisted by my own daddy’s hands.”

“Did it make you sad?” I wondered, but Alphie Mae shook her head.

“No, it made me proud,” she confessed. “I sat there on that pretty mown grass, smellin’ the sweet scent of clover. Bees were buzzing around a few feet away, the sun shinin’ like a gold trophy in the sky, and I told my mama what we’d done, my daddy and I, walkin’ from Kansas to Colorado, takin’ on no-account scoundrels in a wagon train attack, buildin’ a cabin with our bare hands, makin’ a new life in the wilderness, and I was proud.”

And rightly so, I thought. I was a little bit proud myself to discover I knew a woman, who as a child, had made her way across a wild, largely uninhabited expanse of the United States of America to settle in a primitive forest in the shadows of lofty Rocky Mountain grandeur.

*All rights reserved. No part of the article may be reproduced in any form whatsoever without permission in writing from the author except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.